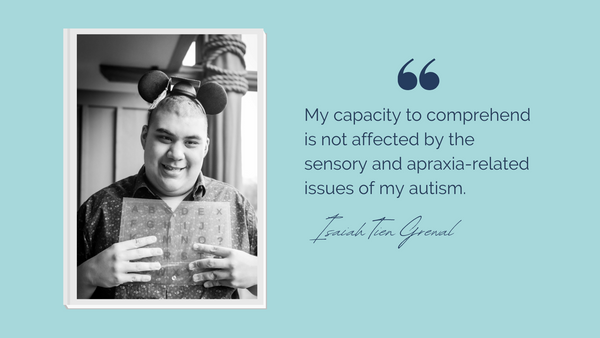

By Isaiah Tien Grewal

My parents did not fully understand me until I was 13. They loved me so much, but for more than a decade, my parents got me wrong because medical professionals got me wrong, teachers got me wrong, and the media got me wrong. This blog will help you get non-speaking Autistics like me right – today. This article explains my experience of nonspeaking autism.

Nonspeaking does not equal nonthinking!

A 2015 study, summarized by United for Communication Choice, found “that autism and apraxia are highly co-morbid: 64% of children [referred for communication delays] initially diagnosed with autism also had apraxia.” Apraxia is a neurological condition obstructing a body from carrying out its brain’s plans, like making the sounds needed to speak reliably. According to NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke), apraxia makes it impossible to “carry out skilled movement and gestures, despite having the physical ability and desire to perform them.”

Autistic nonspeakers are commonly labeled “nonverbal,” but that word means without language, a cognitive ability different from speech. As explained by the International Association for Spelling as Communication, “speech is the physical production of sounds…[and] relies on motor skills to produce, sequence, and mix.” Recent living evidence of nonspeaking Autistics, like me, who can type their thoughts proves the outdated nonverbal classification is wrong. My capacity to comprehend is not affected by the sensory and apraxia-related issues of my autism.

Some common autism therapy goals and methods are flawed

The best autism therapies evolve with current research. Millions of dollars are spent on autism research annually, so any methods that aren’t updated based on the results of that work are off-target. I don’t make these statements lightly – the lives of my trapped nonspeaking friends are at stake. Here are my opinions on three common autism therapies:

Picture-based communication systems (PECS)

Picture communication systems are not enough. A 2013 study, summarized by United for Communication Choice, found “no data exists to support PECS...improving communicative functions beyond requesting.” It’s shocking to me that some still use iterations of a nearly 40-year-old therapy without consideration of newer research!

Full expression using images alone is impossible at any age. Finishing my current college coursework with pictures would be risible. Unfortunately, because too many systems do not want to do the work to update their approach, most of my fellow nonspeakers are trapped in their apraxic bodies, condemned to communicate like toddlers forever.

Speech language therapy for autism

Some autism professionals recommend speaking in phrases one word longer than an Autistic can speak to you. Ignore them and cancel all future appointments! Then go here and get yourself connected to a communication practitioner familiar with autism research published after 2010.

Any speech therapy goal that limits a nonspeaker’s access to advanced cognitive material is nonsense. New studies are now published regularly to prove that “autism is primarily a neuro-motor condition rather than a social or behavioral one” and “that non-speaking individuals cannot be assumed to lack language” (United for Communication Choice). Speech therapy should be solely for practicing the mechanics of making clear sounds and not for gauging readiness to learn more academics. I attested to the agony of erroneous speech therapy goals in my poem Talk Therapy.

Eye contact with autism

Apraxia is a whole-body condition that can also affect a nonspeaker’s ocular motor control. “Responding to their name by looking at the speaker” is a useless therapy goal. Looking at someone is unrelated to hearing them! For me, sometimes when someone says something that makes me happy, I feel compelled to close my eyes to hear it even more. And we all know bobble-headed people who gaze deeply, nod constantly, and yet understand nothing.

Access to reliable communication ASAP is determinative

The ability to fully communicate changes the trajectory of an Autistic’s emotional, academic, and daily life. If your Autistic loved one can't tell you what they’re thinking and feeling, it will become more and more dreadful for them as the years pass trapped inside their bodies.

They want to tell you their hopes and dreams, ask for cuddles when they’re sad, and tell you your breath stinks when necessary. Even mundane conversations, too long left unshared, become chasms of loneliness. School days become unbearable with endless repetitions of material mastered years ago.

Since my parents found my communication teacher more than eight years ago, I've spelled my way to a new life. By typing about the ways apraxia interfered with my muscles not working to eat the foods I wanted to eat, I was finally able to ask for help to “learn the motor” for a healthier diet (I wrote a spelling fluency lesson about that five-year quest here).

I also started learning age-appropriate academics and working toward a dream job in research. To date, I've logged more than 3,000 hours of communication practice and earned an Undergraduate Certificate from Harvard Extension School along the way.

Autism for me is the state of not being able to do everything on the outside that I think about on the inside. Language is a cognitive ability. All humans have thoughts that we don't speak out loud. For nonspeaking Autistics, not being able to reliably speak out our thoughts is a lifelong condition. If you love a nonspeaker, make sure right now is the last moment they will ever feel misunderstood.

About the author:

Isaiah Tien Grewal is a Trainee in the LEND (Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities) Fellowship Program at Stony Brook University and a Neurodiversity and Disability Specialist at Bened Life. He works on research teams at the University of Calgary, the University of Virginia, the University of Toronto, and the Kennedy Krieger Institute (affiliated with Johns Hopkins Medicine). He holds an Undergraduate Certificate from Harvard Extension School and appears in the award-winning short film LISTEN, produced by Communication First. He contributed Chapter 39 of the book, “Leaders Around Me: Autobiographies of Autistics Who Type, Point, and Spell to Communicate,” and was featured in the University of Toronto Magazine and the News of the Stony Brook University School of Social Welfare.

Also by Isaiah Tien Grewal

Dyspraxia and Autism: Two Real-Life Perspectives

Restaurants for All: An Autistic's Advice

Watch the video about Isaiah's life-changing experience with PS128 here

2 comments

Thank you for taking the time to write this out and post it!

Isaiah,

Thank you SO very much for sharing your story! This is truly inspirational and I can’t express how happy I am that you found your purpose and passion, despite the difficulties you’ve experienced. This article of yours will truly help so many.

A friend of mine’s 3-year-old daughter recently became diagnosed with nonverbal autism. I’m going to share your story to her and I think this will help give her a better and brighter understanding for her daughter’s future.

You are truly a blessing!